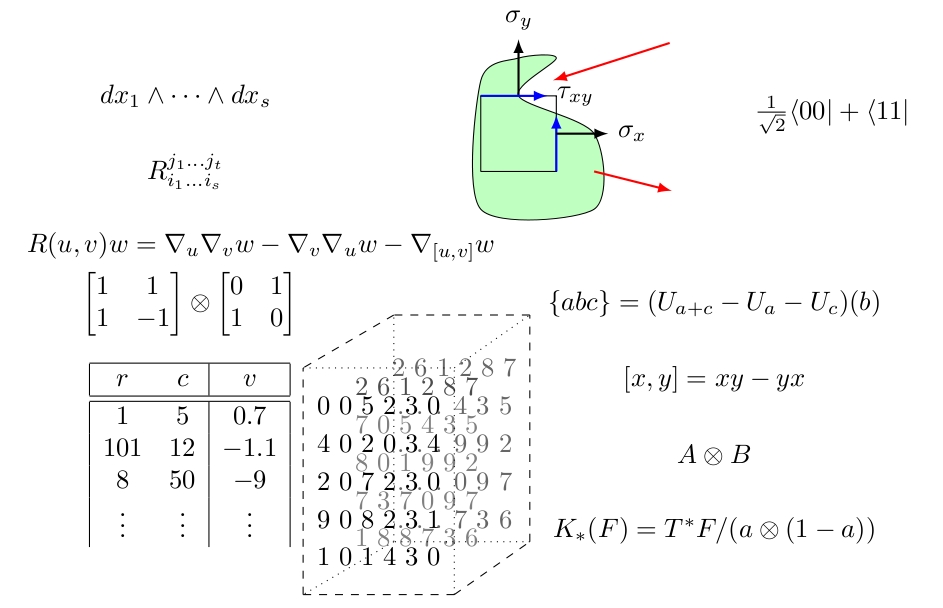

| Era | 1860 | 1900 | 1940 | 1980 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensors are … | Lengths | Forms | Froms & Spaces | Grids, Forms, Spaces, & Multilinear maps | …all things distributive. |

| Used by… | Hamilton | Geometry, Physics | Geometry, Kinematics, Relativity, Quantum Physics, Algebra, Analysis | Finite Geometry, Differential Geometry, Kinematics, Relativity, Quantum Mechanics, Representations, Algebras, PDEs, Categories, Model Theory, Informatics, Statistics | Finite Geometry, Differential Geometry, Kinematics, Relativity, Quantum Mechanics, Representations, Algebras, PDEs, Sensors, Categories, Morley Rank, Isomorphism, Informatics, Statistics, Big Data, Machine Learning, Compression, Data Structures, Clustering, Decompositions, Dimension Reduction, Image Processing, Synthizing Data, Scanning,…and all the uses of which we haven’t a clue! |

From lengths to grids

In 1866 Sir William Hamilton published a treatise in three volumes titled Elements of Quaternions. In this he introduced us to the words vector, scalar, tensor, quaternions, and a host of less familiar terms. He also introduced the axioms of a vector space and gave classical geometry as a model for the axioms. By the ubiquity of these words alone it is clear Hamilton’s ideas had a lasting influence. However several of the concepts have drifted to take on wildly different meaning. Tensors is one of these concepts.

What was Hamilton’s concept of a Tensor?

Before answering we should say tensors were not all that important to Hamilton’s account. Key instead were versors: quaternion vectors of length $1$ (Book II Section 8). Hamilton demonstrated versors could be represented as points on the sphere. Multiplication by versors rotated other vectors in space by the angles of the relative position of the versor on the sphere. Indeed, versor – from the same root word that gave us reverse – roughly translates to “twister”. Hamilton’s use of “tensors” was as the lengths (norms) of a quaternions (Book II Section 11). Multiplying by a general quaternion (instead of versor) would turn the space and then apply a “tension”, i.e. stretch or shrink, by the amount measured by the tensor. So tensors were merely lengths and at least geometrically the cause of the least novel action of his newly created quaternions.

The limiting factor to Hamilton’s creativity was his focus on recasting all geometry in terms of his quaternions. This imposed an artificial restriction to $3$-dimensions which was unnatural even to his quaternions. Removing this dependence would radically transform Hamilton’s tensors and it happened almost imperceptibly.

Tensor take over versors

Hamilton’s contemporaries had many existing uses for “tensors”, what today we mostly call of his newly invented term vectors. E.g. Cauchy modeled curvature on a curve $s$ in space by the formula \(\begin{aligned} \kappa & = \left\|\left(\frac{dx}{ds},\frac{dy}{ds},\frac{dz}{ds}\right)\right\|=\sqrt{\frac{dx}{ds}^2+\frac{dy}{ds}^2+\frac{dz}{ds}^2}. \end{aligned}\) where $T(s)=(x(s),y(s),z(s))$ is a path of tangents along the curve. This curvature is naturally described as one of Hamilton’s tensors – he spent much of Book III translating these concepts into his language. Here is a sample that he draw attention in his book’s preface and lead others to mimic.

…$\rho’’$ (for $T\rho’=1$) may be called the Vector of Curvature, because its tensor $T\rho’’$ is a numerical measure for what is usually called the curvature at a point $P$ and its versor $U\rho’’$ represents the ultimate direction of the semidiameter $PC$

Hamilton Book III, Article 389 (4)

Many formulas of this sort would soon be called tensors on account of being lengths of vectors and for reasons that connected to the geometric or scientific applications like stretching, tension, curving etc.. Versors being directions were often left as too contextual and the focus quickly turned to discussing only the “tensors”.

Index Calculus

By the time of the later geometers Christoffel, Levi-Civita, Ricci, Riemann tensors were linked with curvature conceptually. This meant that as curvature and other geometric quantities diversified and expanded into multi-dimensional measures of matrices of partial derivatives. There was apparently no reason to return to a versor styled vocabulary but instead the term tensor began to encompass any computations with curvature. Tensors were no longer lengths, they are tools to measure shape.

Physics too was exhibiting measurements of tension in grids such as stress and pressure. The lower-dimensional analogs having been adapted to the tensor vocabulary, it made sense now to discuss any one of these grids measuring stress/tension/curvature as a \emph{tensor}, e.g. by Voigt (See Voigt 20.2).

Between 1900 and 1938 tensors were grids of numbers, or grids of functions that could when evaluated produce grids of numbers – such as grids of directional derivatives. The Ricci and Levi-Civita notation of subscripts and superscripts (also known as index-calculus) dominated calculations with occasional modification by Einstein — who omitted the writing of summations — and Dirac who knitted the concepts of duality into the fabric of tensor analysis.

But there was a problem. This generalization happened unfortunately without any of the firm guidance of proper definitions and axioms as Hamilton himself had done with the introduction of terms like vector, scalar, versor, and tensors. There were several unspoken assumptions that would trigger the invention of a third interpretation of tensors.

From grids to products

So is every grid of numbers deserving of the title tensor? Right away the answer was understood to be no. It should be emphasized that even today tensor should not be grasped as mere grids of numbers either. However it was clear that many authors struggled to articulate in a robust way what more they demanded of a tensor. Here we read the definition from Sokolnikoff Tensor Analysis 1951 which follows in roughly the same wording as his predecessors.

Tensor analysis is concerned with a study of abstract objects, called tensors, whose properties are independent of the reference frames used to describe the objects.

Despite ambiguity in terms like “properties” and “independent” it is evident from this quote, and from examples of the time, that to qualify as a tensor one needs a (reference) frame. In a grid of numbers it is easy to guess what the frame should be: its length, width, height etc. Today we call these axes or legs of a tensor. Also this grid must be regular: no row is longer or shorter than another.

Now as to the concept of independence from the frame, each axes has a dimension equal to the dimension of a vector space. For example, $(3\times 2)$-matrix $M$ is relating a $2$-dimensional space with a $3$-dimensional space. Independence means to investigate this matrix without coordinates, but while somehow maintaining a notion of rows verses columns. That is it will not do to think of a $(3\times 2)$-matrix as a vector in $\mathbb{R}^6$ but neither do want to be wed to the fixed coordinate system of matrices. It was complicated to describe.

What changed in 1938 is that Hassler Whitney wrote down specific rules and constructions for the combining of multiple vector spaces in a manner that grids of numbers would be representable in a rigorous axiomatic model. He called this the tensor product. He taught us how to build \(\mathbb{R}^3\otimes \mathbb{R}^2\) It wasn’t matrices because we think of the left and right as coordiante-free vector space. But even in the notation we kept track of the two original spaces. The clever trick was to attach a function from these spaces into this new object, i.e. \(\otimes:\mathbb{R}^3\times \mathbb{R}^2\rightarrowtail \mathbb{R}^3\otimes \mathbb{R}^2.\) This brought back algebra to the study of tensors.

Monoidal Categories

Owing perhaps to Whitney’s very general treatment, tensor products where swept up in the wave of categorical abstractions that followed in the 1940’s. This made them critical early examples of universal properties and building blocks of many further fundamental categorical and algebraic structures. No longer where sets needed, $\otimes$ became a binary product on a category defined through how it interacted with object especially $\hom$. The key ingredient being Kan’s notion of adjunction \(\hom(C\otimes B, A)\cong \hom(C,\hom(B,A)).\) If $(-)\otimes B$ can be defined as adjoint to $\hom(B,-)$ then we can generalize tensors to almost any structure. History has been a little more restrained than this but nevertheless “tensor” in algebra is now somewhat synonymous with “tensor product” and is characterized almost entirely in abstract form having nothing to do with grids of numbers and even less to do with lengths of vectors.

One side effect however is that the abstractions demanded greater background in algebra than a simple treatment of grids of numbers. Even today most texts present tensor products as depending on general notions of modules, freeness, and bilinear maps. That is hardly necessary and delays the introduction of a natural tool. As noted in this article, tensor products can be introduced with nothing more than undergraduate linear algebra.

The historical acceptance of the algebraic universal product notions of tensors and the grid of numbers view of tensors has remained a growing divide between fields of study. But a recent advent is steering both perspective towards a common theme once more.

The return of the grids

Statisticians have always understood the role of grids of data. Here is a demonstration of 5-tensor: it has 2-axes of draws, each draw is filled with 2-D charts filed one after the other for a total of 5-axes.

P. McCullagh took the initiative to translate the well-understood history of tensor like statistical research into the formal language of tensors. But arguably it is the raise of data collection that has driven renewed focus on how tools for tensors might be applied more broadly. In engineering circles the questions are about extracting basis-invariant information – relatives of eigen theory and singular value decompositions, diagonalization, and such. This has also attracted the interests of theorist who see within tensors numerous complexity puzzles. The ability compute determinants efficiently while closely related polynomials like permanents remain hard. The exponent in the complexity of matrix multiplication and the differences between P and NP have each been studied with the lens of tensors as grids of numbers. Meanwhile entire programming languages aimed at Neural Networks are based fundamentally on tensors. Here the data needs a tensor in the sense of grids of numbers, but the computations and data structures rely more on the algebraic conceptions of tensor product spaces.

This is where we are today with tensor.

Additional Questions?

If you have additional questions, feel free to reach out to a maintainer / contributor on the contact page.