An undergraduate is prepared when he or she understands a coset.

A graduate student is prepared when he or she understand a tensor product.– Alexander Kleshchev, shared in jest.

So is it true that tensor products are graduate work? Maybe if we insist on teaching it the way Whitney introduced it. But what follows is a low-tech matrix based definition that can be given in an undergraduate linear algebra course. Keep in mind that today many industries use tensors much earlier in careers than ever before. So even if this effort does not meet your standards it is worth making some effort to simplify.

If you never understood a tensor product this article is for you. If you already know what a tensor is and you have to teach someone else, then this article is also for you. Last, if you ever plan to calculate with tensors than our coordinate based version is for you.

The tensor product with coordinates

Let \(\mathbb{R}\) be the coefficients of our tensor – if you know of other commutative rings use whatever you like here. Let us assume \(\mathbb{R}^a\) is a list (a row) vector and \(v^{\top}\) denote a transpose.

\begin{gather*} \otimes:\mathbb{R}^a\times \mathbb{R}^b\rightarrowtail \mathbb{M}_{a\times b}(\mathbb{R}) \qquad v\otimes u := v^{\top}u. \end{gather*}

For example with $v=(1,7)$ and $u=(1,2,3)$ we get

\begin{gather*} v\otimes u = \begin{bmatrix} % IMPORTANT 1: need the space after the 4 backslashes. otherwise will not render. % IMPORTANT 2: Need no space between “7” and the newline character, otherwise will not render. % IMPORTANT 3: Need 4 backslashes in markdown, which gets outputted in HTML as 2 backslashes, which is read as a newline in the bmatrix environment. % Optional: Instead of using newlines, can place everything in 1 line at the cost of looking messy. 1\\ 7 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3\\ 7 & 14 & 21 \end{bmatrix}. \end{gather*}

What is\(\rightarrowtail\)? It special notation for the distributive property.

Observation 1. This is a distributive product.

\[ v\otimes (u+u’) = v^{\top}(u+u’) =v^{\top}u+u^{\top}u’ =v_\otimes u+v\otimes u’. \]

Likewise on the left. It is also linear in the left, and the right variable in the following sense:

\[ v\otimes (\alpha u) = \alpha(v\otimes u) = (\alpha v)\otimes u. \]

In fact these three observation could be taken together are called bilinear. As an abstract definition of a tensor product. This is known sometimes as the Universal Mapping Property for tensor products.

Theorem If \(\circ:\mathbb{R}^{a}\times \mathbb{R}^{b}\rightarrowtail \mathbb{R}^{c}\) is distributive (\(\mathbb{R}\)-bilinear) then there is a linear map

\[ \hat{\circ}: \mathbb{M}_{a\times b}(\mathbb{R})\to \mathbb{R}^{c} \]

such that

\[ v\circ u = \hat{\circ}(v\otimes u). \]

Proof. Let \({e_1,\ldots,e_a}\) be a basis of \(\mathbb{R}^a\) and \({f_1,\ldots,f_b}\) be a basis of \(\mathbb{R}^b\). Then

\[ \hat{\circ}(e_i\otimes f_j) = \hat{\circ}(E_{ij}) := e_i\circ f_j. \]

Here \(E_{ij}\) is the \((a\times b)\)-matrix with zero every except at \(ij\) where it is \(1\). Evidently \({E_{ij}}\) is a basis of \(\mathbb{M}_{a\times b}(\mathbb{R})\) so we have defined \(\hat{\circ}\) on a basis. \(\Box\)

Remark. For those in the know: we haven’t avoided free modules. We still use a basis, but we haven’t needed to add in additional relations such as \((v_2+v'_2,v_1)-(v_2,v_1)-(v'_2,v_1)\) and others in order to create \(V_2\otimes V_1\). Matrices already include the necessary relations. If it seems this is a trick solely possible for fields then take a look at our later section.

Observation 2.

No matter what you pick, \(v_2\otimes v_1\) is a matrix of rank 1. If we row reduce we are in a sense mapping \( (1,7)\mapsto e_1=(1,0) \) and indeed the above matrix is row-reduced to:

\[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3\\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \]

Likewise if we column reduce we map \(u=(1,2,3)\) to \(f_1=(1,0,0)\) and get

\[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0\\ 7 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \]

And if map \(v\otimes u\) to \(e_1\otimes f_1\)

\[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \]

In the algebraic literature tensors \(v\otimes u\) are called various things include simple tensors or pure tensors. It is a pity. When we recognize this as rank, rank of a matrix, we recognize that simple tensors are just the bottom of a hierarchy of types of tensors. Also it makes it clear we can compute this number and it helps us instantly see the dimension and a basis of a tensor product.

That is it. We have made a tensor product of two vector spaces. Some call this an outer product but tensor product really is the right name in general.

Tensor products with relations.

This was almost too easy. Why don’t we try something a bit harder. For example lets assume an audience now that knows of quotients, for example \(\mathbb{Z}/12={0,1,2,\ldots,11}\), i.e.: the time of day which is cyclical and resets every 12 hours, and letting \(0\) be \(12\). The let us make more creative lists of vectors (modules technically).

\begin{align*} V_2 & = \mathbb{Z}/3\oplus\mathbb{Z}/6\\ V_1 & = \mathbb{Z}/2\oplus \mathbb{Z}/6\oplus \mathbb{Z}/12 \end{align*}

How should we form \(V_2\otimes V_1\)? Again matrices suffice, but we have to fold in the concept of an ideal.

First lets write out the above quotients in detail with exact sequences.

\[ 0\to \{(3a,6b)\mid a,b\in \mathbb{Z}\} \longrightarrow \mathbb{Z}\oplus\mathbb{Z}\longrightarrow V_1\to 0 \]

\[ 0\to \{(2a,6b,12c)\mid a,b,c\in \mathbb{Z}\} \longrightarrow \mathbb{Z}\oplus\mathbb{Z}\oplus\mathbb{Z} \longrightarrow V_2 \to 0 \]

Vertically we take the tensor product of the \(\mathbb{Z}\)’s creating

\[ \otimes : \mathbb{Z}^{\oplus 2}\times \mathbb{Z}^{\oplus 3}\rightarrowtail \mathbb{M}_{2\times 3}(\mathbb{Z}). \]

This is a distributive product, and to make quotients of distributive products we need ideals. Ideals are subspaces that absorb products on the right, such as

\begin{align*} R & := \{(3a,6b)\mid a,b\in \mathbb{Z}\}\otimes \mathbb{Z}^{\oplus 3}\\ & = \left\{ \begin{bmatrix} 3a & 3b & 3c \\ 6d & 6e & 6f \end{bmatrix} \middle| a,b,c,d,e,f\in \mathbb{Z}\right \} \end{align*}

left ideals absorb products on the left

\begin{align*} L & := \mathbb{Z}^{\oplus 2}\otimes {(2a,6b,12c)\mid a,b,c\in \mathbb{Z}}\\ & = \left\{ \begin{bmatrix} 2a & 6b & 12c\\ 2d & 6e & 12 f \end{bmatrix}\middle| a,b,c,d,e,f\in \mathbb{Z}\right \} \end{align*}

So to make 2-sided ideal we add these together:

\begin{align*} I := R+L = \left\{ \begin{bmatrix} 1a & 3b & 3c\\ 2d & 6e & 6f \end{bmatrix}\middle| a,b,c,d,e,f\in \mathbb{Z}\right \} \end{align*}

Definition.

\begin{align*} V_2\otimes V_1 = \mathbb{M}_{2\times 3}(\mathbb{Z})/I \\ \begin{bmatrix} \mathbb{Z}/1 & \mathbb{Z}/3 & \mathbb{Z}/3 \\ \mathbb{Z}/2 & \mathbb{Z}/6 & \mathbb{Z}/6 \end{bmatrix} \end{align*}

Some may wish to check this against other treatments.

\begin{align*} (\mathbb{Z}/3\oplus \mathbb{Z}/6)&\otimes (\mathbb{Z}/2\oplus \mathbb{Z}/6\oplus \mathbb{Z}/12) \\ & =(\mathbb{Z}/3\otimes (\mathbb{Z}/2\oplus \mathbb{Z}/6\oplus \mathbb{Z}/12))\oplus (\mathbb{Z}/6\otimes (\mathbb{Z}/2\oplus \mathbb{Z}/6\oplus \mathbb{Z}/12)) \\ & =(\mathbb{Z}/1\oplus \mathbb{Z}/3\oplus \mathbb{Z}/3)\oplus (\mathbb{Z}/2\oplus \mathbb{Z}/6\oplus \mathbb{Z}/6). \end{align*}

For those who know what to expect, we get what we expect. And again we have not had to begin with the free module \(\mathbb{Z}[V_2\times V_1]\) and throw in an enormous number of relations. In fact the matrix model we have used is an ideal choice for computation.

Tensor products with many spaces

We can iterate the above definition

\[ K^{d_3}\otimes K^{d_2}\otimes K^{d_1} := K^{d_3}\otimes (K^{d_2}\otimes K^{d_1}) \]

Its elements are 3-way arrays. If you build it inductively it would make the following distributive product.

But why not define things this way?

\[ K^{d_3}\otimes K^{d_2}\otimes K^{d_1} := (K^{d_3}\otimes K^{d_2})\otimes K^{d_1} \]

This hits at problem in Whitney’s definition as a binary product. It is popular to define tensor products as binary operations \(U\otimes V\) and then argue for relations such as associativity and commutativity, e.g. arguing that there is no material difference between our two definitions.

\[ (K^{d_3}\otimes K^{d_2})\otimes K^{d_1} \cong K^{d_3}\otimes (K^{d_2}\otimes K^{d_1}) \]

This can be done but there is an obvious alternative with coordinates. We can define a ternary tensor product whose elements look like this.

Tensors with general modules

For more complicated modules \(V_i\) we of course have more to do. Suppose \(V_i=\langle x_1,\ldots,x_{d_i}\rangle\). Then there is a surjective homomorphism

\[ \pi_i:K^{d_i}\to V_i \]

and \(R_i:=\ker \pi_i\) embeds into \(K^{d_i}\) so that we get an exact sequence

\[ 0\to R_i\to K^{d_i}\to V_i\to 0. \]

It would be fine to have an infinite number of generators as well. Putting this together we get the ingredients of a general tensor.

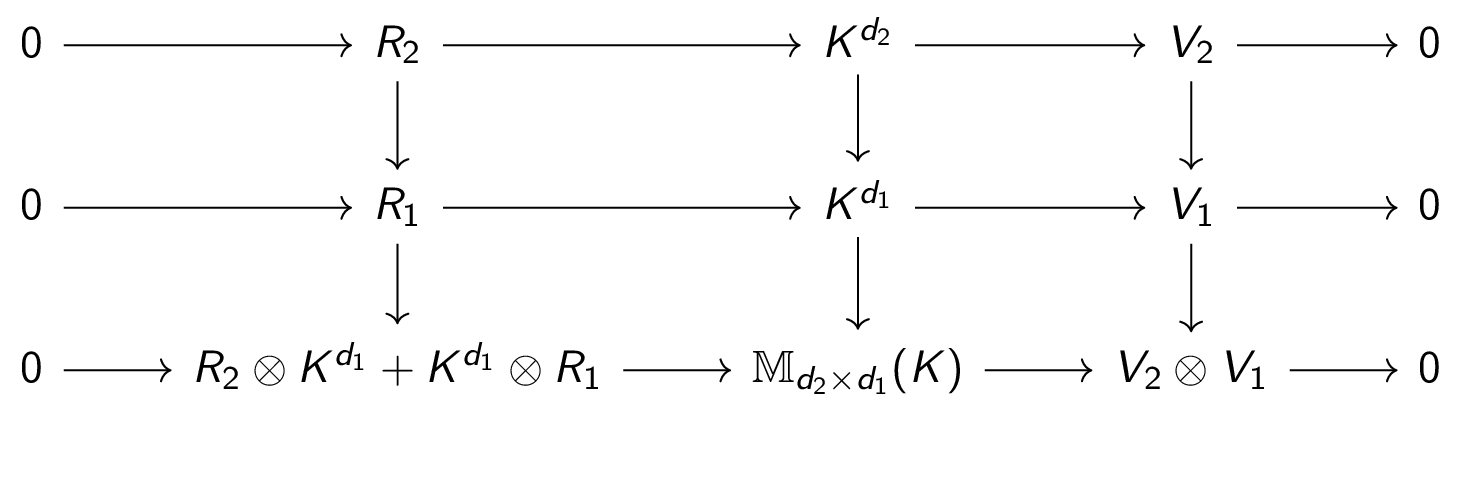

The horizontal lines are exact sequences and the vertical lines are Curryed maps, i.e.

\[ K^{d^2}\to (K^{d_1}\to \mathbb{M}_{d_2\times d_1}(K)) \]

In the usual convention of Currying one drops the parenthesis once the context of the notion has been set. So in the diagram the vertical lines are bilinear maps.

What is happening here is the concept of an ideal. Ideals are substructures of products that absorb products on the left and on the right. The set \(R_2\otimes K^{d_1}\) absorbs \(K^{d_1}\) acting on the right, and \(K^{d_2}\otimes R_1\) absorbs multiplication by \(K^{d_2}\) on the left. Since

\[ R_2\otimes K^{d_1}+K^{d_2}\otimes R_1 \]

is an ideal of \(\mathbb{M}_{d_2\times d_1}(K)=K^{d_2}\otimes K^{d_1}\), its quotient is a well-defined distributive product

\[ V_2\otimes V_1 := \mathbb{M}_{d_2\times d_1}(K)/(R_2\otimes K^{d_1}+K^{d_2}\otimes R_1). \]

For a ternary tensor product we use three rows, etc.

What is gained by Whitney’s original definition?

The coordinate method of tensor products is amenable to calculations and builds on somewhat simple concepts such as matrices and arrays. Whether or not it is the right place to start is a matter of pedagogical debate and background. So what do we gain by investing in Whitney’s definition?

Whitney’s tensor products are sophisticated coordinate free constructions. They rely on concepts such as universal mapping properties which are often pedagogical goals in their own right. Above all, Whitney’s definition is by now well-known and part of the essential history of the topic.

Additional Questions?

If you have additional questions, feel free to reach out to a maintainer / contributor on the contact page.